Yikes, I can't believe it's Tuesday again! Where does the time go? Soon Christmas will be around the corner. I've been meaning to post some more reviews last week but work has kept me quite busy and any free time has been spent, well, reading voraciously. Don't worry, I promise to post some new content soon. In the mean time, it's time for another round of Top Ten Tuesday hosted by The Broke and Bookish and this week they ask book bloggers to list their most difficult reads. I'm going to include some novels that I started but never finished because those ones exemplify my most painful reading experiences.

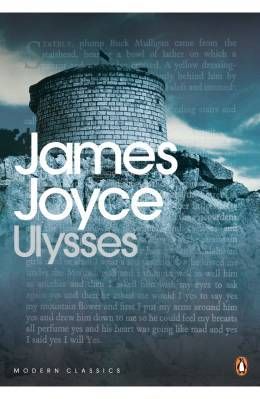

- Ulysses by James Joyce: The constant thorn in my side. This is supposed to be the greatest novel ever written? Balderdash! I've lost count as to how many times I have tried to read this monstrosity only to toss it aside in a fit of rage. This book right here is the apotheosis of literary masturbation. For 800 pages, Joyce wants to prove to the world that he is a literary genius. This may be true but I can never get past chapter three to find out. Oddly enough, I don't despise Joyce as a writer and really enjoyed Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man but Ulysses is beyond my intellectual capabilities, only serving to put me in a foul mood of consternation.

- The Ambassadors by Henry James. I detest Henry James and his convoluted, ostentatious writing style. Enough already with the excessive details and run-on sentences that stretch a full page amounting to nothing of significance! Get to the bloody point, geez! Here is my rant.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: I don't know what it is about his writing exactly but it's aggravating to me. I've tried several times to get past the firsts few chapters but gave up. Sorry Mr. Dickens, looks like you and I aren't meant to be friends.

- Sons and Lovers by D.H. Lawrence: Again, another one of those "classics" that I have tried to finish countless times but failed because it proved far too effective as a sleeping drought. I am big fan of Lawrence's short stories but this novel along with some of the others I have attempted are so tedious and verbose as to drive me mad.

- The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner: Probably the most difficult novel that I have forced myself to read cover to cover. Maybe I am used to Woolf's more elegantly composed stream-of-consciousness but Faulkner's attempt in this style is so rough, jagged, violent and completely incomprehensible. The various time lapses and abrupt jump cuts between past and present left my mind reeling in agony. I might tackle this novel again in the future to see if I am able to make better sense of it.

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte: Ugh. I really had to force myself to finish this novel and came very close to tossing it out the window. I'd rather gouge my eyes out than have to read this rubbish again.

- A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway: Dull. Dull. Dull.

- As for Me and My House by Sinclair Ross: Apparently, this is is a Canadian literary masterpiece. What a joke. I had to read this for class and if anything, it sets Canadian literature back another 50 years. Terrible writing and tedious. Probably one of the worst books I have had the displeasure of reading.

- Catch-22 by Joseph Heller: One of the most overrated 'classics' in my opinion. Not a difficult read by any means, just overlong and repetitive. It's just the same joke over and over and over and over...

- The Waves by Virginia Woolf: My favorite author but this novel puts stream-of-consciousness and free association into overdrive. The writing is achingly beautiful as much as it is utterly perplexing.